Open-ended

The Death of Marcus Fakana and the search for its meaning

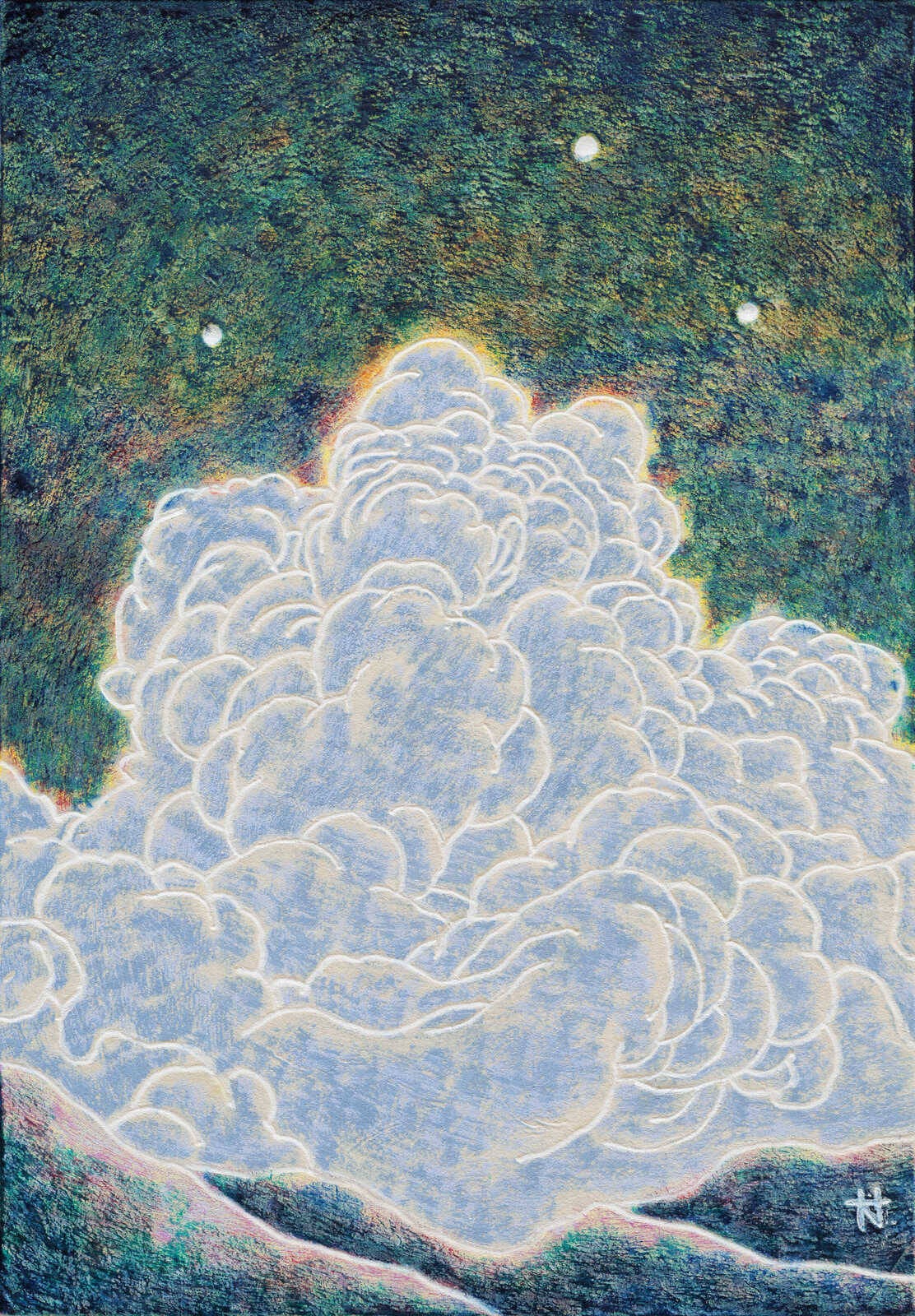

I saw a girl holding a white balloon on the way to the cafe. She was standing with a boy in a grassy patch on a road otherwise paved, half-kissing, half-headbutting him to quell any awkwardness. I stared, wondering if the balloon was for Marcus Fakana. Blue and white balloons were to be released this evening to mark seven days since he died last Friday. ‘Words cannot express the pain that’s felt,’ said a post published by the Instagram handle ‘justiceformarcusf’. But people could stand wherever they found themselves to let go of something fragile, two balloons that would quickly be lost to a sepia sky.

A car Marcus had been travelling in collided with a lorry in the early hours of the morning. His friend had been driving the ‘vehicle of interest’. ANPR had picked out the number plate, and shown the car to be uninsured. They’d outdriven police at 80mph before the car was found crushed on Pretoria road, Tottenham. I read the news last Saturday morning, that Marcus had died aged 19, and three months to the day of his release from a Dubai prison, where he’d been charged with having sex with a 17-year-old girl.

I spoke of my disbelief over the phone. It was one of those odd conversations, where I mentioned that Marcus Fakana had been strengthening his faith while imprisoned, after being reported by the girl’s mother, and before being pardoned by Dubai’s ruling Sheikh. He’d served half of his one-year sentence. We recounted his storyline, we distinguished its patterns.

15 years ago, a week after Marcus Fakana’s fourth birthday, a magnitude 7.0 earthquake destroyed much of Haiti. The chaos was so worst-case, that it felt to be a staged-intervention,

‘It flattened the headquarters of the United Nations mission, which would have taken the lead in coordinating relief,’ wrote former New Yorker writer George Packer at the time, ‘it took down hospitals, wrecked the port, put the airport’s control tower out of action.’ It damaged the Presidential Palace and the National Cathedral. It killed the archbishop.

A conservative televangelist was swiftly aired discussing the ‘pact’ Haitians supposedly signed with the Devil two hundred years ago. Pat Robertson issued broadcasts after every major tragedy of the early-mid 2000s, blaming American evil for 9/11, and American insolence for Hurricane Katrina. There seemed, to him, a locatable explanation for every unfathomable horror. To those others who seldom feel uncertain, ‘there’s no such thing as undeserved suffering. People struck by disaster always had it coming.’

Earlier in the year, while Marcus still exercised and spoke with God in prison, my mum and I shared a morning. She sat in her chair, deepening its parent-shaped indent. I sat on the swivel top, tapping at a spreadsheet from the breakfast bar. We were talking about death and all of its controversies after somebody else had died.

“God man,” my mum had released at the discussion’s peak, as in, ‘how do you reconcile it?’ It was then that I told her about something I’d heard earlier, a paragraph in the bible of various numbers and names, taken from a time when giants still lived, and people lived hundreds of years at a time– a directory of men and their curious ages from a hub of Old Testament families. Where men had lived close to the span of a millennia, one man stood out for surviving only 365 years. ‘Enoch walked with God,’ the bible had said, ‘Enoch walked with God,’ it had said again under his age of death. Enoch had disturbed the pattern. The logic of his life sounded mistaken, and comforting. I told my mum about it to comfort her. She looked on as I shared it, the cogs of her mind privately turning, endeavouring to generate some peace.

I spoke about Marcus over the phone, at a volume for the intricacies of the mic alone. We mulled over the likely explanations, all of them, in some way, blaspheming him; all of them, obvious and vague. To talk about tragedy at all is to play the game of tagging it, to attempt to know it through the eyes of God, or to know God through the letdown of loss. A good person is vulnerable to perpetual suffering for simply living in the world, with all of its malignant complexities. An early end can be an indication of nothing internal; we can find this consoling with audacity and acute desperation.

‘Haitian history is a chronicle of suffering so Job-like that it inevitably inspires arguments with God, and about God,’ George Packer said in his 2010 commentary of Haiti’s utter loss.

Haiti, through its historical relationships with witchcraft and dark arts, slavery and colour caste, gangs and coups, extreme poverty and extreme weather, was brought lower by one of the century’s worst earthquakes, and never recovered. It never rebuilt, thanks to corruption, and a lack of innate resources. Its last president was assassinated four years ago, two years before the death of American televangelist Pat Robertson, who would’ve no doubt seen the coup play out on air. By then, Pat Robertson had long made up his mind, had made his recommendations, and instinctively turned his back. So much of searching for meaning in tragedy, of writing a small story from the patterns and the grooves, is hankering after the peace that comes through certainty, the new page permitted by conclusions. It is a washing of the hands for those of us well-distanced and able. If there is one difference between us and God, it is his natural urge to steward loss, his everpresence, be it our joy or certain despair. We, in contrast, for the health of our own minds, desire to sign off where possible– to leave no thing open-ended, even where it’s tragedy’s design.